When Lorene Smith hears someone call her “Lori,” she knows they’re a Fairfield resident. The name is a milemarker on her life journey, a label she used for 50 years. Today, things are different. Today, she goes by her given name.

“When I meet somebody, I know if they call me Lori, I know there that they’re from Fairfield,” Lorene says. “If they call me Lorene, I know that I met them after I was 50.”

Like those names marking Lorene’s stages in life, her mental health journey has milemarkers, too.

Nearly twenty years ago, at age 55, Lorene received her diagnosis.

“It was the September after [my husband] Tom died in August,” Lorene says. “I was doing very poorly.”

Overwhelmed by grief and loss, Lorene wanted to end it all.

“I stepped out in front of a semi, because I just wanted to be with Tom,” Lorene says. “And I looked up and saw the driver’s face and pulled back — because I thought, ‘If I’m going, I’m not taking anybody with me.’”

After the incident, Lorene visited her family doctor.

“I wanted some medication,” Lorene says. “I wanted something so I could sleep, so I wouldn’t be cryin’ all day long, and I wouldn’t have this terrible pain.”

Lorene’s doctor then asked Lorene what she really wanted. She answered she just wanted to be with Tom.

That led to another milemarker, another conversation with another trusted doctor — someone Lorene knew from her work in human services.

“He gave me a tentative diagnosis as bipolar II — bipolar disease,” Lorene says. “Which I was relieved to hear, because the way I felt my whole life had a name — it never had a name before.”

Names and places — and new faces

As Lorene recalled previous pain, she thought back to the days she was “Lori” — all the way back to her preteen years.

“I was 12,” Lorene says. “The first time I attempted suicide, I stepped out in front of a car. It hit me and just knocked me down — it was a passive suicide attempt, in my opinion.”

A year later, another milemarker. And another name — this time, unspoken and unknown.

“At age 13, I went down from 5’8″ and 130 pounds — in under four months, I was 5’7″ and weighed 85 pounds,” Lorene says. “I spent a month in the hospital for severe malnutrition. Anorexia did not have a name then.”

More years — and more miles — brought Lorene to Fairfield.

“When I was 16, my family moved to Fairfield, Iowa, from Council Bluffs, and Fairfield was going to be my fifth high school,” Lorene says. “I didn’t move with my parents. I put myself on a bus when I had no other options.”

Pulling into the bus stop, seeing the Palmer Motel across the street burning down, Lorene looked out the window. In that moment, her life took a turn for the better.

“I looked out the window and saw Tom, and I knew I was going to marry him — boom, just like that,” Lorene says.

Later, at a local grocery store, Lorene met Tom face-to-face. And she experienced a peace she couldn’t explain.

“Tom took my hand and put his other hand over it, and he said, ‘I’ve been looking forward to meeting you, Lori.’ He knew my name,” Lorene says. “For most of my life, when someone touched me, I would go immediately elbows out and fists, but his hand was warm — it was magical.”

A family recipe

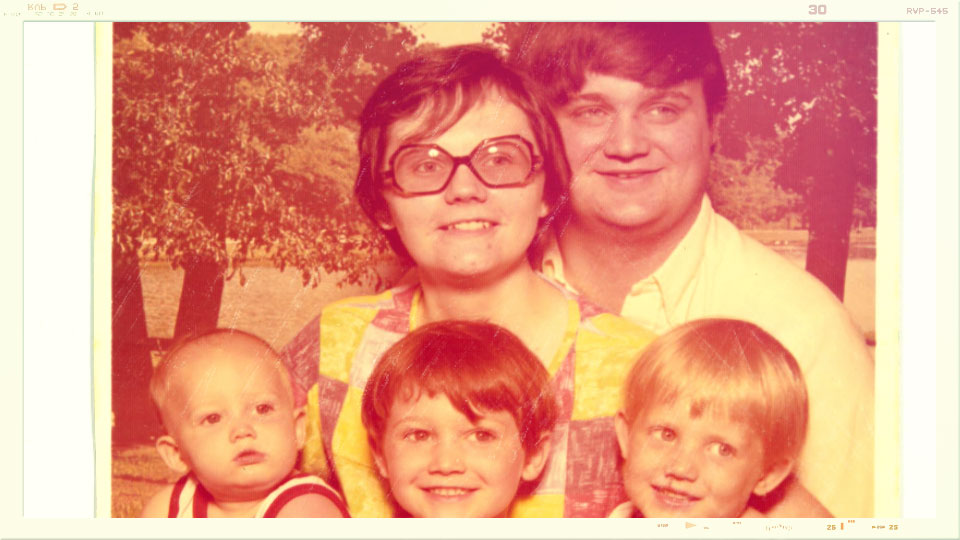

Lorene and Tom married a couple of years later. She was 18; he was 20. Kids followed another couple of years later. More milemarkers.

“We have three boys,” Lorene says. “When they were young and my depression was severe, [Tom] wrote … we called it the recipe, and he wrote out a schedule every fifteen minutes — this is what you do.”

The recipe gave Lorene what she needed — a path to follow, step by step.

“I was well enough that I could follow a schedule,” Lorene says. “[Tom] had things on there like smile, and hug the babies.”

Although Lorene says she was “so sick” when her boys were young, she sees them thriving today — and they’re helping her thrive, too. She credits her late husband — a mainstay — for it all.

“I have sons that are part of my life and are strong, natural supports for me,” Lorene says. “That’s because Tom took care of me. … Because of Tom, I was able to be a mother to my three sons.”

From college to a career

Education was also a large part of Lorene’s journey.

“I was able to go to college and succeed there,” Lorene says. “I got my degree in psychology and sociology, and I got a job … two days after I graduated from college. I was a psychiatric rehabilitation practitioner, and I worked with people with a mental health diagnosis.”

After more than a decade in her position, Lorene reached another milemarker — she joined the Behavioral Health team at Optimae.

“I absolutely loved my job and loved working for Optimae,” Lorene says. “After I retired, I’ve come to the Resource Center — sometimes during the week, but most Fridays. Fridays they play games.”

Lorene says games are an important part of the journey to strong mental health, providing an avenue for socialization, a network of natural supports and an opportunity to build communication skills.

“We play card games like UNO Flip or Yahtzee or Sorry! or UNO No Mercy — and that may seem trivial to some people, but it’s not,” Lorene says. “It’s good socialization. It’s team building. It’s making natural supports for one another.”

Solid, social support

As Lorene has had the opportunity to socialize and form relationships with her peers, she says she knows not everyone has had those same opportunities. And she says that some are reluctant to seek help because of the stigma associated with mental illness.

“Some people simply do not understand mental illness,” Lorene says. “They can’t wrap their minds around the fact that my brain chemistry doesn’t work correctly, and I need medication to balance that out.”

Lorene stresses that mental health support should include three components:

- medical (a counselor, therapist and/or psychiatrist plus medication)

- familial (friends and family)

- personal (self-care)

“The most important component is self-care,” Lorene says. “That’s what you have the most control over.”

Lorene is also quick to add that having a mental illness does not make someone a “bad” person.

“Some people see [a mental illness as] a moral failing that only a certain kind of people have,” Lorene says. “Mental illness is an equal opportunity disease.”

While Mental illness is an equal opportunity disease, Lorene says Optimae’s Recovery and Resource Center fosters an equal opportunity environment — and that brings her back week after week.

“Everyone is welcome here [at the Recovery and Resource Center],” Lorene says. “You don’t have to meet a certain criteria to be here.”

Feeling fully accepted, Lorene says that for her and her friends, Optimae is another family.

“I get as much from Optimae as I’ve ever given — it’s been an honor to work for Optimae,” Lorene says. “And, if you don’t have a good family, then make a family.”

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, help is available. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (988) is a free, confidential resource for people wanting to talk. Take care of a friend, a loved one or yourself. Call, text, or chat with a 988 Lifeline counselor for assistance during difficult moments anytime, day or night.